Weaponization of the term”conspiracy theory”

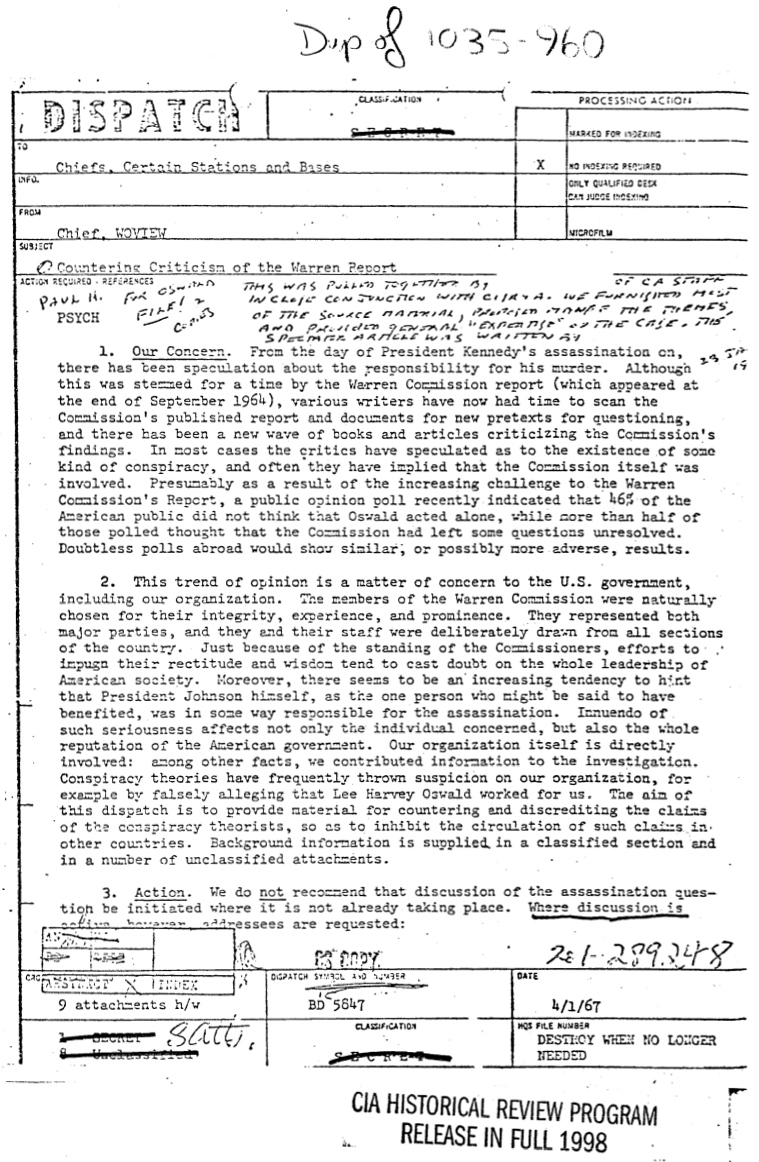

CIA record #104-10406-10110 on “Countering Criticism Of The Warren Report”, Uncovered by a 1976 FOIA request from the New York Times.

PSYCH

1. Our Concern. From the day of President Kennedy’s assassination on, there has been speculation about the responsibility for his murder. Although this was stemmed for a time by the Warren Commission report, (which appeared at the end of September 1964), various writers have now had time to scan the Commission’s published report and documents for new pretexts for questioning, and there has been a new wave of books and articles criticizing the Commission’s findings. In most cases the critics have speculated as to the existence of some kind of conspiracy, and often they have implied that the Commission itself was involved. Presumably as a result of the increasing challenge to the Warren Commission’s report, a public opinion poll recently indicated that 46% of the American public did not think that Oswald acted alone, while more than half of those polled thought that the Commission had left some questions unresolved. Doubtless polls abroad would show similar, or possibly more adverse results.

“Western European critics” see Kennedy’s assassination as part of a subtle conspiracy attributable to “perhaps even (in rumors I have heard) Kennedy’s successor [Johnson].” One Barbara Garson has made the same point in another way by her parody of Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” entitled “MacBird,” with what was obviously President Kennedy (Ken O Dune) in the role of Duncan, and President Johnson (MacBird) in the role of Macbeth.

2. This trend of opinion is a matter of concern to the U.S. government, including our organization. The members of the Warren Commission were naturally chosen for their integrity, experience and prominence. They represented both major parties, and they and their staff were deliberately drawn from all sections of the country. Just because of the standing of the Commissioners, efforts to impugn their rectitude and wisdom tend to cast doubt on the whole leadership of American society. Moreover, there seems to be an increasing tendency to hint that President Johnson himself, as the one person who might be said to have benefited, was in some way responsible for the assassination. Innuendo of such seriousness affects not only the individual concerned, but also the whole reputation of the American government. Our organization itself is directly involved: among other facts, we contributed information to the investigation. Conspiracy theories have frequently thrown suspicion on our organization, for example by falsely alleging that Lee Harvey Oswald worked for us. The aim of this dispatch is to provide material countering and discrediting the claims of the conspiracy theorists, so as to inhibit the circulation of such claims in other countries. Background information is supplied in a classified section and in a number of unclassified attachments.

3. Action. We do not recommend that discussion of the assassination question be initiated where it is not already taking place. Where discussion is active [business] addresses are requested:

a. To discuss the publicity problem with [?] and friendly elite contacts (especially politicians and editors), pointing out that the Warren Commission made as thorough an investigation as humanly possible, that the charges of the critics are without serious foundation, and that further speculative discussion only plays into the hands of the opposition. Point out also that parts of the conspiracy talk appear to be deliberately generated by Communist propagandists. Urge them to use their influence to discourage unfounded and irresponsible speculation.

b. To employ propaganda assets to [negate] and refute the attacks of the critics. Book reviews and feature articles are particularly appropriate for this purpose. The unclassified attachments to this guidance should provide useful background material for passing to assets. Our ploy should point out, as applicable, that the critics are

(I) wedded to theories adopted before the evidence was in,

(II) politically interested,

(III) financially interested,

(IV) hasty and inaccurate in their research, or

(V) infatuated with their own theories.

In the course of discussions of the whole phenomenon of criticism, a useful strategy may be to single out Epstein’s theory for attack, using the attached Fletcher [?] article and Spectator piece for background. (Although Mark Lane’s book is much less convincing that Epstein’s and comes off badly where confronted by knowledgeable critics, it is also much more difficult to answer as a whole, as one becomes lost in a morass of unrelated details.

4. In private to media discussions not directed at any particular writer, or in attacking publications which may be yet forthcoming, the following arguments should be useful:

a. No significant new evidence has emerged which the Commission did not consider. The assassination is sometimes compared (e.g., by Joachim Joesten and Bertrand Russell) with the Dreyfus case; however, unlike that case, the attacks on the Warren Commission have produced no new evidence, no new culprits have been convincingly identified, and there is no agreement among the critics. (A better parallel, though an imperfect one, might be with the Reichstag fire of 1933, which some competent historians (Fritz Tobias, A.J.P. Taylor, D.C. Watt) now believe was set by Van der Lubbe on his own initiative, without acting for either Nazis or Communists; the Nazis tried to pin the blame on the Communists, but the latter have been more successful in convincing the world that the Nazis were to blame.)

b. Critics usually overvalue particular items and ignore others. They tend to place more emphasis on the recollections of individual witnesses (which are less reliable and more divergent Q and hence offer more hand-holds for criticism) and less on ballistics, autopsy, and photographic evidence. A close examination of the Commission’s records will usually show that the conflicting eyewitness accounts are quoted out of context, or were discarded by the Commission for good and sufficient reason.

c. Conspiracy on the large scale often suggested would be impossible to conceal in the United States, esp. since informants could expect to receive large royalties, etc. Note that Robert Kennedy, Attorney General at the time and John F. Kennedy’s brother, would be the last man to overlook or conceal any conspiracy. And as one reviewer pointed out, Congressman Gerald R. Ford would hardly have held his tongue for the sake of the Democratic administration, and Senator Russell would have had every political interest in exposing any misdeeds on the part of Chief Justice Warren. A conspirator moreover would hardly choose a location for a shooting where so much depended on conditions beyond his control: the route, the speed of the cars, the moving target, the risk that the assassin would be discovered. A group of wealthy conspirators could have arranged much more secure conditions.

d. Critics have often been enticed by a form of intellectual pride: they light on some theory and fall in love with it; they also scoff at the Commission because it did not always answer every question with a flat decision one way or the other. Actually, the make-up of the Commission and its staff was an excellent safeguard against over-commitment to any one theory, or against the illicit transformation of probabilities into certainties.

e. Oswald would not have been any sensible person’s choice for a co-conspirator. He was a “loner,” mixed up, of questionable reliability and an unknown quantity to any professional intelligence service.

f. As to charges that the Commission’s report was a rush job, it emerged three months after the deadline originally set. But to the degree that the Commission tried to speed up its reporting, this was largely due to the pressure of irresponsible speculation already appearing, in some cases coming from the same critics who, refusing to admit their errors, are now putting out new criticism.

g. Such vague accusations as that “more than ten people have died mysteriously” can always be explained in some natural way e.g.: the individuals concerned have for the most part died of natural causes; the Commission staff questioned 418 witnesses (the FBI interviewed far more people, conduction 25,000 interviews and reinterviews), and in such a large group, a certain number of deaths are to be expected. (When Penn Jones, one of the originators of the “ten mysterious deaths” line, appeared on television, it emerged that two of the deaths on his list were from heart attacks, one from cancer, one was from a head-on collision on a bridge, and one occurred when a driver drifted into a bridge abutment.)

5. Where possible, counter speculation by encouraging reference to the Commission’s Report itself. Open-minded foreign readers should still be impressed by the care, thoroughness, objectivity and speed with which the Commission worked. Reviewers of other books might be encouraged to add to their account the idea that, checking back with the report itself, they found it far superior to the work of its critics.

Attachment 1

4 January 1967

Background Survey of Books Concerning the Assassination of President Kennedy

1. (Except where otherwise indicated, the factual data given in paragraphs 1-9 is unclassified.) Some of the authors of recent books on the assassination of President Kennedy (e.g., Joachim Joesten, Oswald: Assassin or Fall Guy; Mark Lane, Rush to Judgment [sic]; Leo Sauvage, The Oswald Affair: An Examination of the Contradictions and Omissions of the Warren Report) had publicly asserted that a conspiracy existed before the Warren Commission finished its investigation. Not surprisingly, they immediately bestirred themselves to show that they were right and that the Commission was wrong. Thanks to the mountain of material published by the Commission, some of it conflicting or misleading when read out of context, they have had little difficulty in uncovering items to substantiate their own theories. They have also in some cases obtained new and divergent testimony from witnesses. And they have usually failed to discuss the refutations of their early claims in the Commission’s Report, Appendix XII (“Speculations and Rumors”). This Appendix is still a good place to look for material countering the theorists.

2. Some writers appear to have been predisposed to criticism by anti-American, far-left, or Communist sympathies. The British “Who Killed Kennedy Committee” includes some of the most persistent and vocal English critics of the United States, e.g., Michael Foot, Kingsley Martin, Kenneth Tynan, and Bertrand Russell. Joachim Joesten has been publicly revealed as a onetime member of the German Communist Party (KDP); a Gestapo document of 8 November 1937 among the German Foreign Ministry files microfilmed in England and now returned to West German custody shows that his party book was numbered 532315 and dated 12 May 1932. (The originals of these files are now available at the West German Foreign Ministry in Bonn; the copy in the U.S. National Archives may be found under the reference T-120, Serial 4918, frames E2564824. The British Public Records Office should also have a copy.) Joesten’s American publisher, Carl Marzani, was once sentence to jail by a federal jury for concealing his Communist Party (CPUSA) membership in order to hold a government job. Available information indicates that Mark Lane was elected Vice Chairman of the New York Council to Abolish the House Un-American Activities Committee on 28 May 1963; he also attended the 8th Congress of the International Association of Democratic Lawyers (an international Communist front organization) in Budapest from 31 March to 5 April 1964, where he expounded his (pre-Report) views on the Kennedy assassination. In his acknowledgments in his book, Lane expresses special thanks to Ralph Schoenman of London “who participated in and supported the work”; Schoenman is of course the expatriate American who has been influencing the aged Bertrand Russell in recent years. (See also para. 10 below on Communist efforts to replay speculation on the assassination.)

3. Another factor has been the financial reward obtainable for sensational books. Mark Lane’s Rush to Judgment, published on 13 August 1966, had sold 85,000 copies by early November and the publishers had printed 140,000 copies by that date, in anticipation of sales to come. The 1 January 1967 New York Times Book Review reported the book as at the top of the General category of the best seller list, having been in top position for seven weeks and on the list for 17 weeks. Lane has reportedly appeared on about 175 television and radio programs, and has also given numerous public lectures, all of which serves for advertisement. He has also put together a TV film, and is peddling it to European telecasters; the BBC has purchased rights for a record $45,000. While neither Abraham Zapruder nor William Manchester should be classed with the critics of the Commission we are discussing here, sums paid for the Zapruder film of the assassination ($25,000) and for magazine rights to Manchester’s Death of a President ($665,000) indicate the money available for material related to the assassination. Some newspapermen (e.g., Sylvan Fox, The Unanswered Questions About President Kennedy’s Assassination; Leo Sauvage, The Oswald Affair) have published accounts cashing in on their journalistic expertise.

4. Aside from political and financial motives, some people have apparently published accounts simply because they were burning to give the world their theory, e.g., Harold Weisberg, in his Whitewash II, Penn Jones, Jr., in Forgive My Grief, and George C. Thomson in The Quest for Truth. Weisberg’s book was first published privately, though it is now finally attaining the dignity of commercial publication. Jones’ volume was published by the small-town Texas newspaper of which he is the editor, and Thomson’s booklet by his own engineering firm. The impact of these books will probably be relatively slight, since their writers will appear to readers to be hysterical or paranoid.

5. A common technique among many of the writers is to raise as many questions as possible, while not bothering to work out all the consequences. Herbert Mitgang has written a parody of this approach (his questions actually refer to Lincoln’s assassination) in “A New Inquiry is Needed,” New York Times Magazine, 25 December 1966. Mark Lane in particular (who represents himself as Oswald’s lawyer) adopts the classic defense attorney’s approach of throwing in unrelated details so as to create in the jury’s mind a sum of “reasonable doubt.” His tendency to wander off into minor details led one observer to comment that whereas a good trial lawyer should have a sure instinct for the jugular vein, Lane’s instinct was for the capillaries. His tactics and also his nerve were typified on the occasion when, after getting the Commission to pay his travel expenses back from England, he recounted to that body a sensational (and incredible) story of a Ruby plot, while refusing to name his source. Chief Justice Warren told Lane, “We have every reason to doubt the truthfulness of what you have heretofore told us” Q by the standards of legal etiquette, a very stiff rebuke for an attorney.

6. It should be recognized, however, that another kind of criticism has recently emerged, represented by Edward Jay Epstein’s Inquest. Epstein adopts a scholarly tone, and to the casual reader, he presents what appears to be a more coherent, reasoned case than the writers described above. Epstein has caused people like Richard Rovere and Lord Devlin, previously backers of the Commission’s Report, to change their minds. The New York Times’ daily book reviewer has said that Epstein’s work is a “watershed book” which has made it respectable to doubt the Commission’s findings. This respectability effect has been enhanced by Life magazine’s 25 November 1966 issue, which contains an assertion that there is a “reasonable doubt,” as well as a republication of frames from the Zapruder film (owned by Life), and an interview with Governor Connally, who repeats his belief that he was not struck by the same bullet that struck President Kennedy. (Connally does not, however, agree that there should be another investigation.) Epstein himself has published a new article in the December 1966 issue of Esquire, in which he explains away objections to his book. A copy of an early critique of Epstein’s views by Fletcher Knebel, published in Look, 12 July 1966, and an unclassified, unofficial analysis (by “Spectator”) are attached to this dispatch, dealing with specific questions raised by Epstein.

7. Here it should be pointed out that Epstein’s competence in research has been greatly exaggerated. Some illustrations are given in the Fletcher Knebel article. As a further specimen, Epstein’s book refers (pp. 93-5) to a cropped-down picture of a heavy-set man taken in Mexico City, saying that the Central Intelligence Agency gave it to the Federal Bureau of Investigation on 18 November 1963, and that the Bureau in turn forwarded it to its Dallas office. Actually, affidavits in the published Warren material (vol. XI, pp. 468-70) show that CIA turned the picture over to the FBI on 22 November 1963. (As a matter of interest, Mark Lane’s Rush to Judgment claims that the photo was furnished by CIA on the morning of 22 November; the fact is that the FBI flew the photo directly from Mexico City to Dallas immediately after Oswald’s arrest, before Oswald’s picture had been published, on the chance it might be Oswald. The reason the photo was cropped was that the background revealed the place where it was taken.) Another example: where Epstein reports (p. 41) that a Secret Service interview report was even withheld from the National Archives, this is untrue: an Archives staff member told one of our officers that Epstein came there and asked for the memorandum. He was told that it was there, but was classified. Indeed, the Archives then notified the Secret Service that there had been a request for the document, and the Secret Service declassified it. But by that time, Epstein (whose preface gives the impression of prolonged archival research) had chosen to finish his searches in the Archives, which had only lasted two days, and had left town. Yet Epstein charges that the Commission was over-hasty in its work.

The New York Times daily book reviewer has said that Epstein’s work is a “watershed book” which has made it respectable to doubt the Commission’s findings. This respectability effect has been enhanced by Life magazines 25 November 1966 issue, which contains an assertion that there is a “reasonable doubt,” as well as a republication of frames from the Zapruder film (owned by Life), and an interview with Governor Connally, who repeats his belief that he was not struck by the same bullet that struck President Kennedy.

8. Aside from such failures in research, Epstein and other intellectual critics show symptoms of some of the love of theorizing and lack of common sense and experience displayed by Richard H. Popkin, the author of The Second Oswald. Because Oswald was reported to have been seen in different places at the same time, a phenomenon not surprising in a sensational case where thousands of real or alleged witnesses were interviewed, Popkin, a professor of philosophy, theorizes that there actually were two Oswalds. At this point, theorizing becomes sort of logico-mathematical game; an exercise in permutations and combinations; as Commission attorney Arlen Specter remarked, “Why not make it three Oswalds? Why stop at two?” Nevertheless, aside from his book, Popkin has been able to publish a summary of his views in The New York Review of Books, and there has been replay in the French Nouvel Observateur, in Moscow’s New Times, and in Baku’s Vyshka. Popkin makes a sensational accusation indirectly, saying that “Western European critics” see Kennedy’s assassination as part of a subtle conspiracy attributable to “perhaps even (in rumors I have heard) Kennedy’s successor.” One Barbara Garson has made the same point in another way by her parody of Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” entitled “MacBird,” with what was obviously President Kennedy (Ken O Dune) in the role of Duncan, and President Johnson (MacBird) in the role of Macbeth. Miss Garson makes no effort to prove her point; she merely insinuates it. Probably the indirect form of accusation is due to fear of a libel suit.

9. Other books are yet to appear. William Manchester’s not-yet-published The Death of a President is at this writing being purged of material personally objectionable to Mrs. Kennedy. There are hopeful signs: Jacob Cohen is writing a book which will appear in 1967 under the title Honest Verdict, defending the Commission report, and one of the Commission attorneys, Wesley J. Liebeler, is also reportedly writing a book, setting forth both sides. But further criticism will no doubt appear; as the Washington Post has pointed out editorially, the recent death of Jack Ruby will probably lead to speculation that he was “silenced” by a conspiracy.

10. The likelihood of further criticism is enhanced by the circumstance that Communist propagandists seem recently to have stepped up their own campaign to discredit the Warren Commission. As already noted, Moscow’s New Times reprinted parts of an article by Richard Popkin (21 and 28 September 1966 issues), and it also gave the Swiss edition of Joesten’s latest work an extended, laudatory review in its number for 26 October. Izvestiya has also publicized Joesten’s book in articles of 18 and 21 October. (In view of this publicity and the Communist background of Joesten and his American publisher, together with Joesten’s insistence on pinning the blame on such favorite Communist targets as H.L. Hunt, the FBI and CIA, there seems reason to suspect that Joesten’s book and its exploitation are part of a planned Soviet propaganda operation.) Tass, reporting on 5 November on the deposit of autopsy photographs in the National Archives, said that the refusal to give wide public access to them, the disappearance of a number of documents, and the mysterious death of more than 10 people, all make many Americans believe Kennedy was killed as the result of a conspiracy. The radio transmitters of Prague and Warsaw used the anniversary of the assassination to attack the Warren report. The Bulgarian press conducted a campaign on the subject in the second half of October; a Greek Communist newspaper, Avgi, placed the blame on CIA on 20 November. Significantly, the start of this stepped-up campaign coincided with a Soviet demand that the U.S. Embassy in Moscow stop distributing the Russian-language edition of the Warren report; Newsweek commented (12 September) that the Soviets apparently “did not want mere facts to get in their way.”

Attachment 2

The Theories of Mr. Epstein by Spectator

A recent critic of the Warren Commission Report, Edward Jay Epstein, has attracted widespread attention by contesting the Report’s conclusion that, “although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission,” President Kennedy and Governor Connally were probably hit successively by the same bullet, the second of three shots fired. In his book, Inquest, Epstein maintains (1) that if the two men were not hit by the same bullet, there must have been two assassins, and (2) that there is evidence which strongly suggests that the two men were not hit by the same bullet. He suggests that the Commission’s conclusions must be viewed as “expressions of political truth,” implying that they are not in fact true, but are only a sort of Pablum for the public, Epstein’s argument that the two men must either have been shot by one bullet or by two assassins rests on a comparison of the minimum time required to operate the bolt on Lee Harvey Oswald’s rifle Q 2.3 seconds Q with the timing of the shots as deduced from a movie of the shooting taken by an amateur photographer, Abraham Zapruder. The frames of the movie serve to time the events in the shooting. The film (along with a slow-motion re-enactment of the shooting made on 24 May 1964 on the basis of the film and other pictures and evidence) tends to show that the President was probably not shot before frame 207, when he came out from beneath the cover of an oak tree, and that the Governor was hit not later than frame 240. If this is correct, then the two men would not have been hit longer than 1.8 seconds apart, since Zapruder’s film was taken at a speed of 18.3 frames per second. Since Oswald’s rifle could not have fired a second shot within 1.8 seconds, Epstein concludes that the victims must have been shot by separate weapons Q and hence presumably by separate assassins Q unless they were hit by the same bullet. Epstein then argues that there is evidence which contradicts the possibility of a shooting by a single bullet. In his book he refers to Federal Bureau of Investigation reports stemming from FBI men present at the Bethesda autopsy on President Kennedy, according to which there was a wound in the back with no point of exit; this means that the bullet which entered Kennedy’s back could not later have hit Connally. This information, Epstein notes, flatly contradicts the official autopsy report accepted by the Commission, according to which the bullet presumably entered Kennedy’s body just below the neck and exited through the throat. Epstein also publishes photographs of the backs of Kennedy’s shirt and coat, showing bullet holes about six inches below the top of the collar, as well as a rough sketch made at the time of the autopsy; these pictures suggest that the entrance wound in the back was too low to be linked to an exit wound in the throat. In his book, Epstein says that if the FBI statements are correct Q and he indicates his belief that they are Q then the “autopsy findings must have been changed after January 13 [January 13, 1964: the date of the last FBI report stating that the bullet penetrated Kennedy’s back for less than a finger-length .] .” In short, he implies that the Commission warped and even forged evidence so as to conceal the fact of a conspiracy. Following the appearance of Epstein’s Inquest, it was pointed out that on the morning (November 23rd) after the Bethesda autopsy attended by FBI and Secret Service men, the autopsy doctors learned that a neck wound, obliterated by an emergency tracheostomy performed in Dallas, had been seen by the Dallas doctors. (The tracheostomy had been part of the effort to save Kennedy’s life.) The FBI men who had only attended the autopsy on the evening of November 22 naturally did not know about this information from Dallas, which led the autopsy doctors to change their conclusions, finally signed by them on November 24. Also, the Treasury Department (which runs the Secret Service) reported that the autopsy report was only forwarded by the Secret Service to the FBI on December 23, 1963. But in a recent article in Esquire, Epstein notes that the final FBI report was still issued after the Secret Service had sent the FBI the official autopsy, and he claims that the explanation that the FBI was uninformed “begs the question of how a wound below the shoulder became a wound in the back of the neck.” He presses for making the autopsy pictures available, a step which the late President’s brother has so far steadfastly resisted on the grounds of taste, though they have been made available to qualified official investigators. Let us consider Epstein’s arguments in the light of information now available:

1. Epstein’s thesis that if the President and the Governor were not hit by the same bullet, there must have been two assassins:

a. Feeling in the Commission was that the two men were probably hit by the same bullet; however, some members evidently felt that the evidence was not conclusive enough to exclude completely the Governor’s belief that he and the President were hit separately. After all, Connally was one of the most important living witnesses. While not likely, it was possible that President Kennedy could have been hit more than 2.3 seconds before Connally. As Arlen Specter, a Commission attorney and a principal adherent of the “one-bullet theory,” says, the Zapruder film is two-dimensional and one cannot say exactly when Connally, let alone the President, was hit. The film does not show the President during a crucial period (from about frames 204 to 225) when a sign blocked the view from Zapruder’s camera, and before that the figures are distant and rather indistinct. (When Life magazine first published frames from the Zapruder film in its special 1963 Assassination Issue, it believed that the pictures showed Kennedy first hit 74 frames before Governor Connally was struck.) The “earliest possible time” used by Epstein is based on the belief that, for an interval before that time, the view of the car from the Book Depository window was probably blocked by the foliage of an oak tree (from frame 166 to frame 207, with a brief glimpse through the leaves at frame 186). In the words of the Commission’s Report, “it is unlikely that the assassin would deliberately have shot [at President Kennedy] with a view obstructed by the oak tree when he was about to have a clear opportunity”; unlikely, but not impossible. Since Epstein is fond of logical terminology, it might be pointed out that he made an illicit transition from probability to certainty in at least one of his premises.

b. Although Governor Connally believed that he and the President were hit separately, he did not testify that he saw the President hit before he was hit himself; he testified that he heard a first shot and started to turn to see what had happened. His testimony (as the Commission’s report says) can therefore be reconciled with the supposition that the first shot missed and the second shot hit both men. However, the Commission did not pretend that the two men could not possibly have been hit separately.

c. The Commission also concluded that all the shots were fired from the sixth floor window of the Depository. The location of the wounds is one major basis for this conclusion. In the room behind the Depository window, Oswald’s rifle and three cartridge cases were found, and all of the cartridge cases were identified by experts as having been fired by that rifle; no other weapon or cartridge cases were found, and the consensus of the witnesses from the plaza was that there were three shots. If there were other assassins, what happened to their weapons and cartridge cases? How did they escape? Epstein points out that one woman, a Mrs. Walther, not an expert on weapons, thought she saw two men, one with a machine gun, in the window, and that one other witness thought he saw someone else on the sixth floor; this does not sound very convincing, especially when compared with photographs and other witnesses who saw nothing of the kind.

d. The very fact that the Commission did not absolutely rule out the possibility that the victims were shot separately shows that its conclusions were not determined by a preconceived theory. Now, Epstein’s thesis is not just his own discovery; he relates that one of the Commission lawyers volunteered to him: “To say that they were hit by separate bullets is synonymous with saying that there were two assassins.” This thesis was evidently considered by the Commission. If the thesis were completely valid, and if the Commissioners Q as Epstein charges Q had only been interested in finding “political truth,” then the Commission should have flatly adopted the “one-bullet theory,” completely rejecting any possibility that the men were hit separately. But while Epstein and the others have a weakness for theorizing, the seven experienced lawyers on the Commission were not committed beforehand to finding either a conspiracy or the absence of one, and they wisely refused to erect a whole logical structure on the slender foundation of a few debatable pieces of evidence.

2. Epstein’s thesis that either the FBI’s reports (that the bullet entering the President’s back did not exit) were wrong, or the official autopsy report was falsified. a. Epstein prefers to believe that the FBI reports are accurate (otherwise, he says, “doubt is cast on the accuracy of the FBI’s entire investigation”) and that the official autopsy report was falsified. Now, as noted above, it has emerged since Inquest was written that the FBI witnesses to the autopsy did not know about the information of a throat wound, obtained from Dallas, and that the doctors’ autopsy report was not forwarded to the FBI until December 23, 1963. True, this date preceded the date of the FBI’s Supplemental Report, January 13, 1964, and that Supplemental Report did not refer to the doctors’ report, following instead the version of the earlier FBI reports. But on November 25, 1966, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover explained that when the FBI submitted its January 13 report, it knew that the Commission would weigh its evidence together with that of other agencies, and it was not incumbent on the FBI to argue the merits of its own version as opposed to that of the doctors. When writing reports for outside use, experienced officials are always cautious about criticizing or even discussing the products of other agencies. (If one is skeptical about this explanation, it would still be much easier to believe that the author(s) of the Supplemental Report had somehow overlooked or not received the autopsy report than to suppose that that report was falsified months after the event. Epstein thinks the Commission staff overlooked Mrs. Walther’s report mentioned above, yet he does not consider the possibility that the doctors’ autopsy report did not actually reach the desk of the individuals who prepared the Supplemental Report until after they had written Q perhaps well before January 13 Q the draft of page 2 of that report. Such an occurrence would by no means justify a general distrust of the FBI’s “entire investigation.”) b. With regard to the holes in the shirt and coat, their location can be readily explained by supposing that the President was waving to the crowd, an act which would automatically raise the back of his clothing. And in fact, photographs show the President was waving just before he was shot. c. As to the location of the hole in the President’s back or shoulder, the autopsy films have recently been placed in the National Archives, and were viewed in November 1966 by two of the autopsy directors, who… [The last page released ends here.]

Dispatch To: Chiefs, Certain Stations and Bases From: Chief, Subject:

Warren Commission Report: Article on the Investigation Conducted by District Attorney Garrison

Date: 19 July 1968

1. We are forwarding herewith a reprint of the article “A Reporter At Large: Garrison”, published in THE NEW YORKER, 13 July, 1968. It was written by Edward Jay Epstein, himself author of a book (“Inquest”), critical of the Warren Commission Report.

2. The wide-spread campaign of adverse criticism of the U.S., most recently again provoked by the assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy, appears to have revived foreign interest in the assassination of his brother, the late President Kennedy, too. The forthcoming trial of Sirhan, accused of the murder of Senator Kennedy, can be expected to cause a new wave of criticism and suspicion against the United States, claiming once more the existence of a sinister “political murder conspiracy”. We are sending you the attached article Q based either on first-hand observation by the author or on other, identified sources Q since it deals with the continuing investigation, conducted by District Attorney Garrison of New Orleans, La. That investigation tends to keep alive speculations about the death of President Kennedy, an alleged “conspiracy”, and about the possible involvement of Federal agencies, notably the FBI and CIA.

3. The article is not meant for reprinting in any media. It is forwarded primarily for your information and for the information of all Station personnel concerned. If the Garrison investigation should be cited in your area in the context of renewed anti-U.S. attacks, you may use the article to brief interested contacts, especially government and other political leaders, and to demonstrate to assets (which you may assign to counter such attacks) that there is no hard evidence of any such conspiracy. In this context, assets may have to explain to their audiences certain basic facts about the U.S. judicial system, its separation of state and federal courts and the fact that judges and district attorneys in the states are usually elected, not appointed: consequently, D.A. Garrison can continue in office as long as his constituents re-elect him. Even if your assets have to discuss this in order to refute Q or at least weaken Q anti-U.S. propaganda of sufficiently serious impact, any personal attacks upon Garrison (or any other public personality in the U.S.) must be strictly avoided.

Warren Commission Report. (1964). The Science News-Letter

Plain numerical DOI: 10.2307/3947618

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Oswald, L. H.. (2016). The warren commission reports. ABA Journal

JOHNSTON, J. H.. (2019). The Warren Report. In Murder, Inc.

Plain numerical DOI: 10.2307/j.ctvhrd0vs.28

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Fetzer, J. H.. (2004). Disinformation: The Use of False Information. Minds and Machines

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1023/B:MIND.0000021683.28604.5b

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Show/hide publication abstract

“The distinction between misinformation and disinformation becomes especially important in political, editorial, and advertising contexts, where sources may make deliberate efforts to mislead, deceive, or confuse an audience in order to promote their personal, religious, or ideological objectives. the difference consists in having an agenda. it thus bears comparison with lying, because ‘lies’ are assertions that are false, that are known to be false, and that are asserted with the intention to mislead, deceive, or confuse. one context in which disinformation abounds is the study of the death of jfk, which i know from more than a decade of personal research experience. here i reflect on that experience and advance a preliminary ‘theory of disinformation’ that is intended to stimulate thinking on this increasingly important subject. five kinds of disinformation are distinguished and exemplified by real life cases i have encountered. it follows that the story you are about to read is true.”

HAMSHER, J. H., GELLER, J. D., & ROTTER, J. B.. (1968). INTERPERSONAL TRUST, INTERNAL-EXTERNAL CONTROL, AND THE WARREN COMMISSION REPORT. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

Plain numerical DOI: 10.1037/h0025900

DOI URL

directSciHub download

Show/hide publication abstract

“PREDICTED acceptance of the warren commission report among students from 2 measures of personality presumably independent of political attitudes: interpersonal trust and belief in internal vs. external control of reinforcement. both are conceptualized in social learning theory as broad generalized expectancies. each personality test and the warren commission questionnaire were given to students at widely spaced times by different es. ss with consistent attitudes of disbelief of the warren report were significantly less trusting and more external. within sexes, trust is a predictor for males and females, but internal-external control only for males. the study adds to the literature on the contribution of personality variables to understand public reactions to sociopolitical events. (19 ref.) (psycinfo database record (c) 2006 apa, all rights reserved). © 1968 american psychological association.”